First Nations, cities say B.C. has known how to fix Highway of Tears for years

Posted May 19, 2014 1:00 am.

This article is more than 5 years old.

VANCOUVER – Sally Gibson has been waiting nearly two decades for answers about what became of her niece, a 19-year-old forestry student from a small First Nation in northern British Columbia who vanished along the Highway of Tears.

There’s the official story: Lana Derrick was out with some friends and at some point ended up in a car with two unidentified men, with whom she was last seen at a gas station along Highway 16 near Terrace in the early morning of Oct. 7, 1995.

But that’s just one of the many theories, rumours and guesses Gibson and her relatives have heard over the years, a painful reminder that no one — not the family, not the police — has any idea about what happened.

“We have heard so many different stories and have been told so many different things that we don’t even know,” said Gibson from her home in Gitanyow, the First Nations reserve where Derrick grew up.

“It isn’t like Lana died and we went and buried her and the pain will go away. She totally disappeared. That’s an open wound.”

Derrick’s disappearance brought her family into a community of loss and despair, joining the relatives of at least 18 women and girls who disappeared or were murdered along Highway 16 and two adjacent highways.

There are the yearly walks. The memorial ceremonies. And the shared frustration that the provincial government has yet to act on dozens of recommendations to protect vulnerable women in B.C.’s north.

First Nations groups and municipal officials say the province should have acted years ago using a blueprint it already has: a 2006 report with 33 recommendations to improve transportation, discourage hitchhiking, and prevent violence against aboriginal women and girls.

That report was endorsed by a public inquiry report released in December 2012, which called for urgent action.

The 2006 report was crafted by several First Nations groups after the Highway of Tears Symposium.

Its first recommendation was a shuttle bus network along more than 700 kilometres of Highway 16 that runs from Prince Rupert to Prince George.

Other recommendations included education for aboriginal youth, improved health and social services in remote communities, counselling and mental health teams made up of aboriginal workers, more comprehensive victims’ services, and, of course, money to pay for it all.

Wendy Kellas, who works on the Highway of Tears issue for Carrier Sekani Family Services, wants provincial funding to examine whether any of the recommendations need to be updated. For example, the report called for more phone booths along the highway, while the focus now would be on mobile phone coverage, she said.

Still, she said most of the 2006 recommendations remain relevant, including the need for better services not only for aboriginal women, but also for the families of the murdered and missing.

And the proposed shuttle service is needed as much as ever, she said. For First Nations women who can’t afford their own vehicle, there are still few options if they need to travel for groceries, appointments or to visit family.

“I believe it is still necessary,” said Kellas.

“It would have to be a system, very co-ordinated to make sure people in the more rural communities are able to get into the urban centres for the basic necessities of life.”

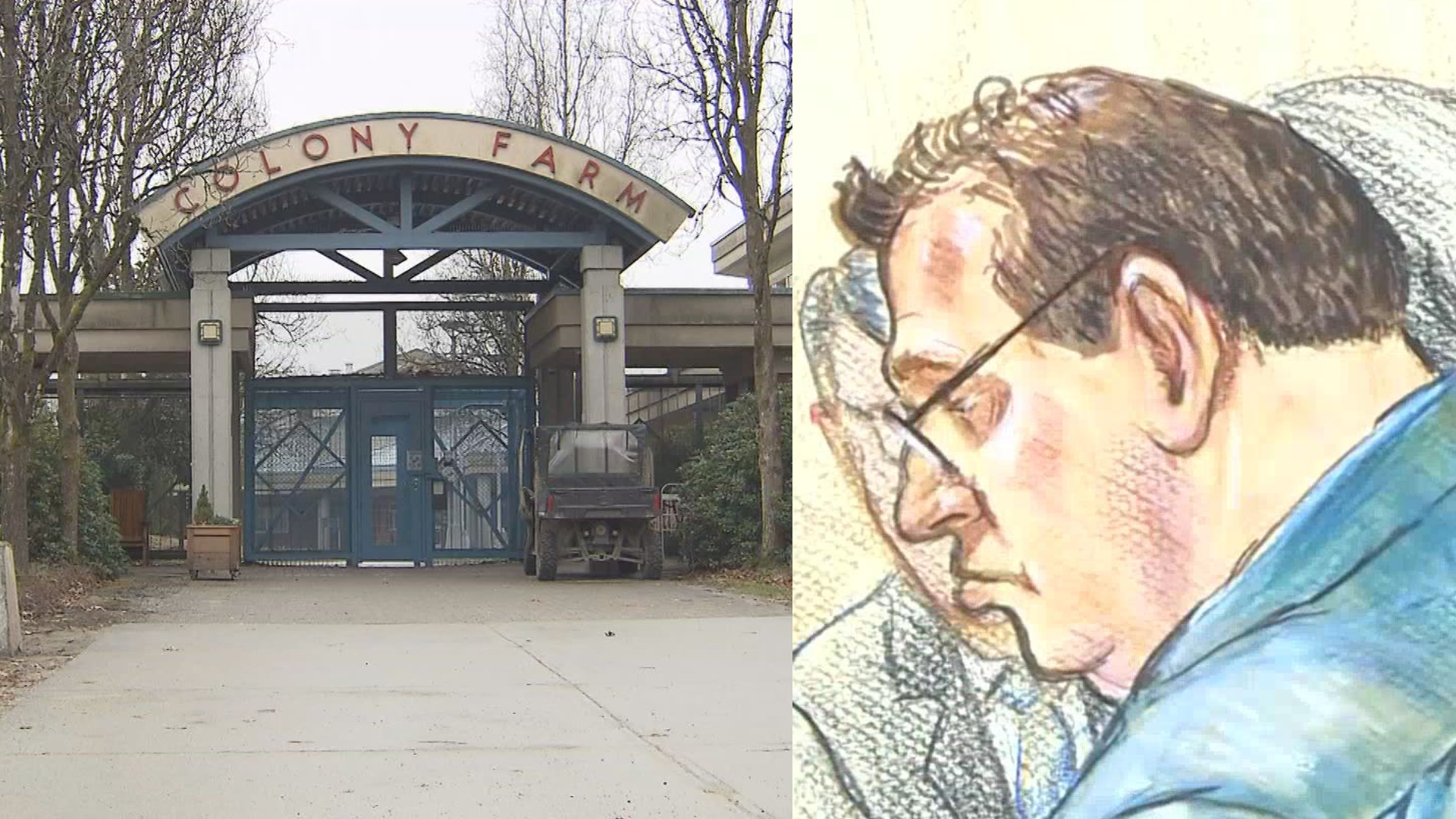

The 2006 symposium was revived by a public inquiry that examined both the Robert Pickton serial killer case and the broader issue of murdered and missing women.

Commissioner Wally Oppal called for immediate action to improve transportation along the Highway of Tears and said the government should implement the 2006 recommendations.

But there has been little effort to hold consultations, and internal government briefing notes revealed work on the file was stalled for much of the past year. The province said it had to put its work on hold when families of women in the Pickton case launched lawsuits last year.

Justice Minister Suzanne Anton and Transportation Minister Todd Stone have declined repeated requests for interviews.

Anton insists the highway is safe, pointing transportation options including a health shuttle for medical patients and Greyhound bus service, which was dramatically cut last year.

Taylor Bachrach, the mayor of Smithers, said Anton appears to be suggesting nothing more needs to be done.

“Some of her comments seem to be trying to justify the status quo or suggest the status quo is adequate,” said Bachrach.

“Transportation in the north is worse than I’ve ever seen it.”

Nevertheless, Bachrach said he’s hopeful the province will actually start its long-delayed Highway of Tears consultations soon.

Transportation Ministry staff planned to attend a meeting with the Omineca Beetle Action Coalition, of which Bachrach is a member, last Friday, and Bachrach said he expected more such meetings to follow.

“I am keen to give the government the benefit of the doubt. If they’re willing to work on this, I think communities are, too.”